Is hallucination-free AI code possible?

And what does that even mean?

In July 2024, I gave a talk on the science of contagion at the 65th International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) in Bath. The IMO is the leading mathematical competition for high school students. Each year, it brings together students from each country who’ve already passed a series of selection tests. As well as having the honour of speaking to some of the brightest young mathematicians from around the world, I also found it fun to include a lot more mathematical nuggets than I’d usually put in a public lecture.

That particular IMO competition would end up being more significant than I’d realised. The following week, DeepMind announced that its AlphaProof and AlphaGeometry models had been able to solve four out of six problems that had been posed in the 2024 contest, equivalent to silver medal-level standard. It was the first time AI had managed to achieve this performance.

The following year, DeepMind would do even better, with an advanced version of Gemini achieving gold-medal standard under IMO exam conditions. Here’s one of the questions it managed to solve:

“A line in the plane is called sunny if it is not parallel to any of the x-axis, the y-axis, and the line x + y = 0. Let n ⩾ 3 be a given integer. Determine all nonnegative integers k such that there exist n distinct lines in the plane satisfying both of the following:

for all positive integers a and b with a + b ⩽ n + 1, the point (a, b) is on at least one of the lines; and

exactly k of the n lines are sunny”

A Lean, keen, proving machine

Last November, DeepMind published a paper in Nature that outlined how AlphaProof had achieved its high performance in the 2024 Olympiad. First, human experts had translated the non-geometry problems from natural language into a formal mathematical representation using the Lean software language. Once in Lean, AlphaProof could work on the problem while being forced to spell out every logical step in a machine-verifiable form.

For example, rather than just stating that ‘the sum of two even numbers is even,’ a proof would explicitly have to show that each number equals two times another number and that their sum is therefore two times some number. Then Lean could automatically check that each step obeys the rules of logic.

Once AlphaProof had done its work, humans then translated the proof back into natural language. This process of learning, suggesting and checking took 2-3 days of computation. So while silver medal standard, it wouldn’t have passed under exam conditions. In contrast, Gemini Pro – with some additional mathematical training – managed to ace the exam in 2025 within the 4.5 hour time limit.

The IMO-specific success of AlphaProof, AlphaGeometry and Gemini is impressive. But how helpful are these kinds of approach beyond the realm of mathematical logic and proof?

One real-life area where checkable and logically consistent AI outputs would be valuable is computer code. After all, the Lean approach works because people have converted mathematical equations from natural language to computer code and back.

Which raises the question: what do we mean by ‘correct’ computer code?

From proofs to programming

A key challenge when transitioning from checking narrow mathematical logic to ensuring ‘hallucination-free’ code is deciding what should be verified. A mathematical proof can be checked at each point to ensure it follows logical steps and is consistent with the definitions given and results already shown. But writing good code isn’t necessarily so structured as a task.

As an illustration, suppose we want to get AI to generate code for a ‘gravity model’ of population movements. The idea behind this model is that people are drawn to places depending on how close and populous they are, much like larger, denser planets have a stronger gravitational pull. If you live in a city, you’ll probably spend little time in the surrounding towns; if you live in a village, you might visit a nearby town more often than a city further away.

(The gravity model can be traced to Belgian engineer Henri-Guillaume Desart. His 1846 analysis using the model suggested that there would be a lot of demand for local railway trips in his country. Unfortunately, this idea would be ignored by rail operators on the other side of the channel; the British railway network would arguably have been far more efficient had it not been for this oversight.)

I started by giving Claude the following request:

Build a gravity model in R with 5 populations with different hypothetical sizes and distances. Plot the flow of people based on the output of this model.

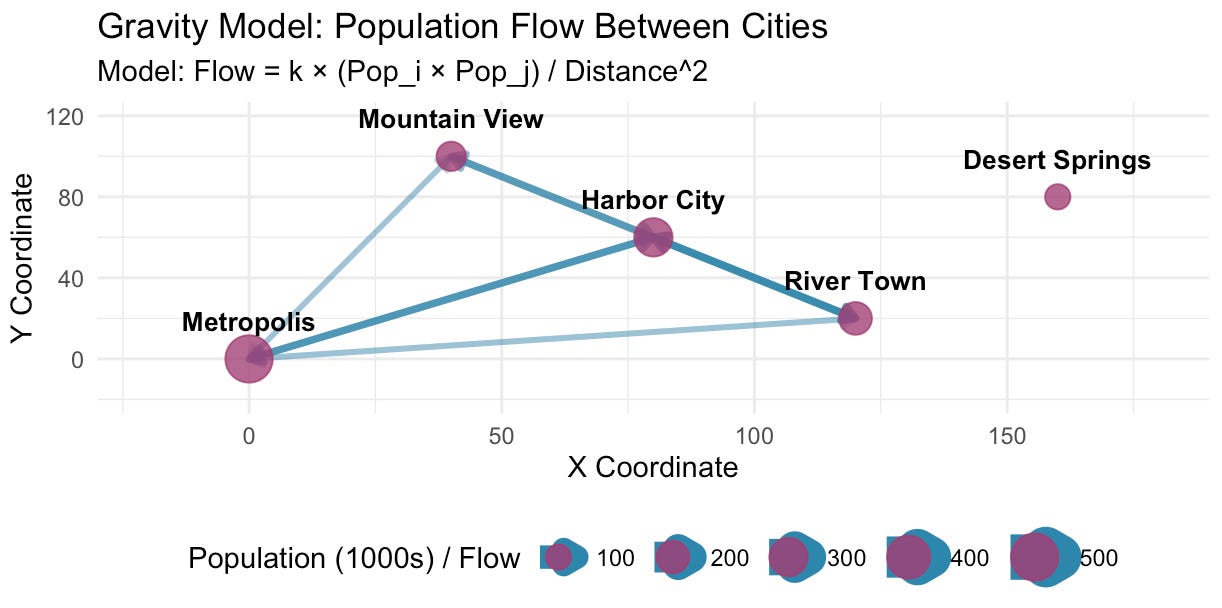

When I ran the code, it produced a plot with two panels. The first showed the hypothetical cities and the population flow between them:

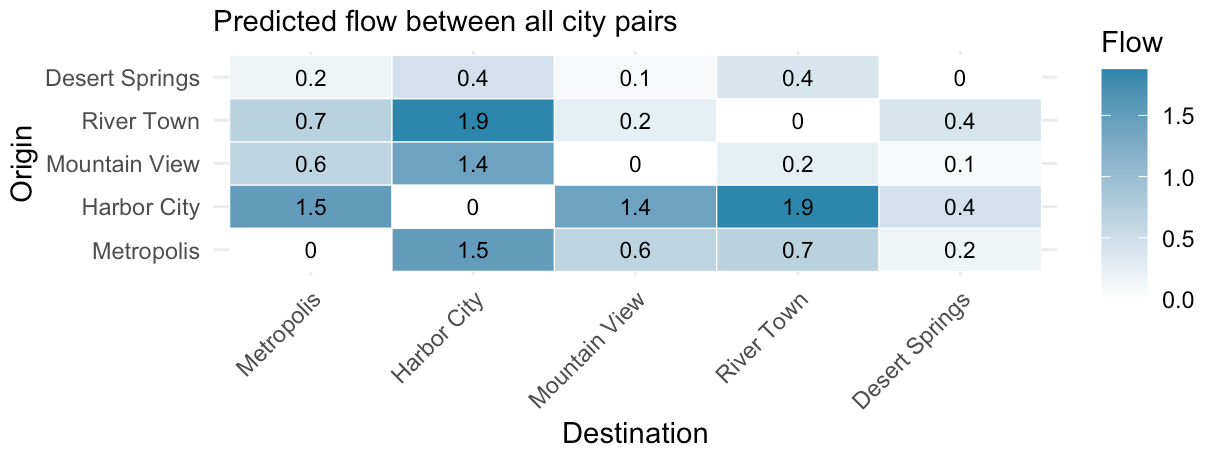

The second panel showed flow values for each origin-destination pair:

Is this code a good outcome?

When it comes to checking AI generated code, there are several different ways we could define ‘correct’ in a way that could be tested automatically. Here are five increasingly demanding notions of correctness:

1. The code runs

If AI has given us some code, then at a minimum it should run without throwing an error. The code above worked, which meets this basic standard.

Similar approaches are already in use for scientific research. For example, a team at the University of Cambridge run the CODECHECK system, which verifies that the code published alongside academic papers runs and outputs the same values as in the paper itself. But CODECHECK is clear about what it does and doesn’t do. In particular, it doesn’t check the method is conceptually correct, and that it doesn’t produce strange edge cases.

2. Check style and formatting of code

Another common top-level code check is to verify that the generated code meets established style and formatting conventions, such as naming, indentation, structure, and documentation. Such checks are not so much about the ‘correctness’ of the code per se, but about readability and usability. And a benefit is that they can be enforced automatically through a static analysis tool (a ‘linter’).

3. Check internal code consistency

If we ask AI for a model of population flow between five cities, then there are several automated checks that we could perform to ensure the code is internally consistent with this request. For example, the gravity model should include population sizes and locations for five cities, and the model should have 5 x 5 = 25 total rates of flow defined. In software terms, this would be a form of ‘structural validation’, ensuring that the model is consistent.

4. Input/output validation

Even if the model code is structurally consistent, we need to check that results make sense. One way to do this is see how outputs change when we vary the inputs. For example, given two cities with known populations and distance, we could first pre-calculate the mathematically correct value. Then we could write a ‘unit test’ that ensures the function in the code responsible for estimating flow produces this value when given the input. This doesn’t guarantee that the function will never produce a strange result, but it does increase confidence that it’s doing what it should.

But there’s a limitation to such checks. They rely on the user knowing (or calculating) an established input-output relationship for the model they’re using. If you’ve never used a gravity model before, you’d either have to implement the equation yourself to check the result, or trust AI to check it for you.

5. Sense checks for qualitative behaviour of model

Suppose that instead of a gravity model, we’d asked for an alternative population mobility process, like a competing destinations model or radiation model. Even if we haven’t worked with a specific model before, there are still properties we might expect. For example, if the distance between two location decreases, mobility should typically increase in a model. And if population sizes are positive, then each pair of cities should have a flow connecting them.

You may have noticed in the first plot above that ‘Desert Springs’ doesn’t have any flow connecting it to other cities. But in the second plot, all the entries in origin-destination grid have a value greater than zero (excluding entries on the diagonal where origin = destination). So there must be a problem somewhere between the model calculation and the plotting output.

A closer look at the code revealed the problem: Claude had made a unilateral decision to omit small population flows from the plot. They are there in the model; we just can’t see them in the visualisation.

When you spend a lot of time working with models, you soon learn to do intuitive qualitative checks like this. If an MSc student shows me a plot based on a flawed model, I can often estimate roughly where in the code things are going wrong without having to look at the code itself.

When asked, Claude explained the reason that one city had no flow connecting it to other cities. Still, someone has to know to ask in the first place. Human specialists can be very efficient at these kinds of qualitative sense checks for new models. But they are tricky to encode as automated checks, because there are so many possible ways that code decisions could produce something odd.

Automation and assumptions

I suspect Lean-style verification methods will soon be able to pick up almost all logical flaws in some fields (e.g. maths exams), and foundation models like Gemini will increasingly get better at doing this without having to first convert natural language to a formal mathematical representation.

Yet they may still struggle to produce ‘correct’ models independently. After all, my above list of proposed checks focuses on tasks that could be automated to ‘prove’ aspects of the code are working correctly, much like Lean imposes automated structure on mathematical proofs. This could help pick up many basic coding errors in fields where models often have predictable structures and logic.

But such checks are not the full story. Building a model isn’t just about having something that can output predictions in a consistent way. It’s about ensuring assumptions are defensible and design decisions are appropriate. Claude might have given me reasonable-if-flawed code for a gravity model, but a great scientific collaborator would have asked what I wanted to use this model for in the first place.