The first book I wrote was probably the hardest piece of work I’ve ever done, closely followed by my second book. My third and latest book was easier from a kind-of-know-how-it-works point of view, but this was heavily offset from a having-two-small-children perspective.

Overall, my three books each took between 20 and 30 months to get to a finished first draft. Some full-time authors can manage it faster, but this seems to be the pace that works for me writing in my spare time alongside a day job. Here’s a plot of the net words I wrote (and deleted) each month since starting:

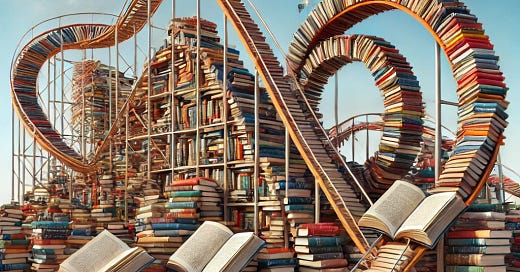

As you can see, those months aren’t all equal. And nor is the experience of writing; there are some major ups and downs along the way. The below is a brief tour of the rollercoaster.

This book is an amazing idea

Non-fiction books start with a proposal; if an editor likes it, they’ll offer a deal to write the full book. So, it’s crucial to start with an idea you are really enthusiastic about. No editor wants to buy a tepid concept, and no author wants to have to spend years of their life writing about one. So the journey begins at the top of a mountain that you think is excellent. Which means there’s only one way to go next.

How do you write a book anyway?

Every time I’ve got a new book deal, I’ve had a brief moment of panic that I don’t actually know how to write a book1. This was obviously excusable when writing my first book, but I’ve had a very similar stumbling point with the others. If anything, the feeling is now amplified because I know I’ve managed it before, and I can see all the earlier files on my computer. Was this really the chapter plan I worked off last time? How on earth did I collate those four hundred papers and articles for that chapter? Will I ever write a pun that good again?

At some point, I should really write down the exact process I go through when getting a new book off the ground. But for now, I’ll have to live with future Adam being annoyed with past Adam for making him work it out again.

Fortunately, there are a couple of lessons that have stuck with me. One is the importance of batching time together. Books take a lot of time to write: once I factor in research, interviews etc, it took me at least 10 hours per 1000 words produced on the page (so a first draft of a book is probably around 1000 hours work total). But I’ve found there was an inefficiency in using occasional free moments for writing. If I have half an hour spare, it will take me twenty minutes to get back up to speed, followed by ten minutes of writing, then a much longer chunk of frustration afterwards.

So long trips have been my friend. Five-hour train to Scotland? Twenty-four hours of travel to Australia? All with no decent wi-fi? That was my productivity zone.

But it wasn’t all productive. Another key lesson I’ve learned is that the end of the first quarter of the book is the hardest.

And I mean really hard.

This book is going to be terrible and will never work

Writing a book is a bit like doing a jigsaw. Except, unlike an actual jigsaw, you have to carve out all the pieces from scratch then work out how they fit together. The toughest point comes when you’ve carved enough pieces to be committed, but not enough to have a clear picture.

What on earth am I going to do with all these scattered pieces of a story?

It’s too late to start again. How can this possibly fit together into a coherent book?

But I’ve learned that there’s also a solution to this dilemma: find the most interesting pieces of the puzzle, pick up the phone, and dig a little deeper.

There are some great stories here

The world is full of fascinating, underappreciated perspectives. As authors, it’s our job to find them. While writing, I’ve somehow managed to track down many of the right people and ask many of the right questions – and they’ve been kind enough to share their time with answers.

I’m not an interviewer, but my one piece of advice to new writers would be to over-research and indulge your genuine curiosity. For example, working on The Perfect Bet, I talked to some people who’d made a fortune by pioneering scientific betting in recent decades. But I didn’t ask them a single question about how many zeros were on their winnings. Because, for me, it wasn’t that interesting exactly how much they’d made; I wanted to know how they’d done it. And, I suspect, my readers would want to know that too.

In short: be curious, dig deeper, and let people share their stories.

How will I ever fill all these gaps?

As the jigsaw pieces fall into place, some gaps will linger. You’ll try and jam one piece into another, then another, before realising that some sections just need some focused work to smooth the rough edges. In contrast, other sections require a long walk – and thinking about something else completely – before a crucial new piece of inspiration hits.

And some pieces, well, will need the harshest decision of them all.

What am I going to do with that beautifully written section that just doesn’t feel right?

Delete it. That’s what you’re going to do. Eventually, anyway. After dithering for ages about whether it’s salvageable. I spent the best part of a weekend finessing the final paragraph of my first book. Then, on reflection, I decided to get rid of it all.

Instead, I went back the stories I’d collated, and realised the ending I’d needed was there all along.

Why are there so many clunky phrases and grammatical errors?

Writing isn’t the same as editing. You’ll have a segment with a wonderful story, or a unique idea, then you’ll re-read it and… it will just not flow properly. Who wrote this jarring nonsense?

The only solution is to spend time editing. Unlike trying to fit writing into stolen moments, I’ve found the same isn’t true of editing. Even a few minutes can be useful for making progress. So most of my books have been edited during my commute. Delete. Move. Replace. Tweak. Repeat.

You know what, maybe this book is actually kind of… good?

The view often looks better from afar. A few months after finishing a book, and a many more months before it comes out, I’ll re-read chunks and realise that it’s not entirely terrible. Sometimes I’ll even read an entire section without noticing, because I’ve somehow managed to create something really quite readable.

Then, over the coming years, people will mention things they’ve spotted in my book that they liked. Things I’d almost forgotten I’ve written. And I’ll be thankful for the person all those years ago who gave up their evenings and weekends and holidays. And wrote on cramped planes and trains.

Then, I’ll start work on the next book, and curse him for not noting more down.

My new book Proof: The Uncertain Science of Certainty is available to pre-order now.

If my editor is reading this: don’t worry, it’s very brief and I soon realise I’ve got it all under control.

Adam, thank you for sharing such an experience; it is way more stressful than writing research papers. I think authors need to be appreciated more. I remember my epi Prof told me that he only received so little from the publishers (and his epi textbook was a standard text internationaly at that time).

Seems highly relatable to my first book experience.