Sometimes a scientific claim lingers, despite evidence to the contrary. One such ‘zombie statistic’ is the idea that immunity to a given SARS-CoV-2 virus wanes rapidly. It still dominates many discussions about COVID, leading to flawed assumptions, and in some cases, inadvertently fuelling conspiracy theories.

A persistent claim about transient immunity

How did it become so widely believed that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 wanes much faster than it does in reality?

I suspect there were three main reasons:

1. Inappropriate early thresholds

In early antibody studies in 2020, the definition of antibody ‘positive’ was often calibrated on severely ill patients in early 2020; patients whose immune systems would have been working in overdrive. Milder cases would therefore test negative, or sometimes positive after an initial post-infection antibody boost, then negative once these antibodies had declined slightly. In other words, some of the early antibody test criteria were not sensitive enough to pick up smaller but still relevant antibody levels.

I’ve noticed that when many people imagine antibody responses over time, they seem to have a consistently declining pattern in mind. But a more realistic shape is what’s known as a ‘set point’ dynamic. Whether we’re looking at dengue or influenza or SARS-CoV-2, we typically see an initial boost, then some decline, before antibodies stabilise at a set point level. For example, here are antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2 over time after a 2nd and 3rd vaccine dose from a US cohort study:

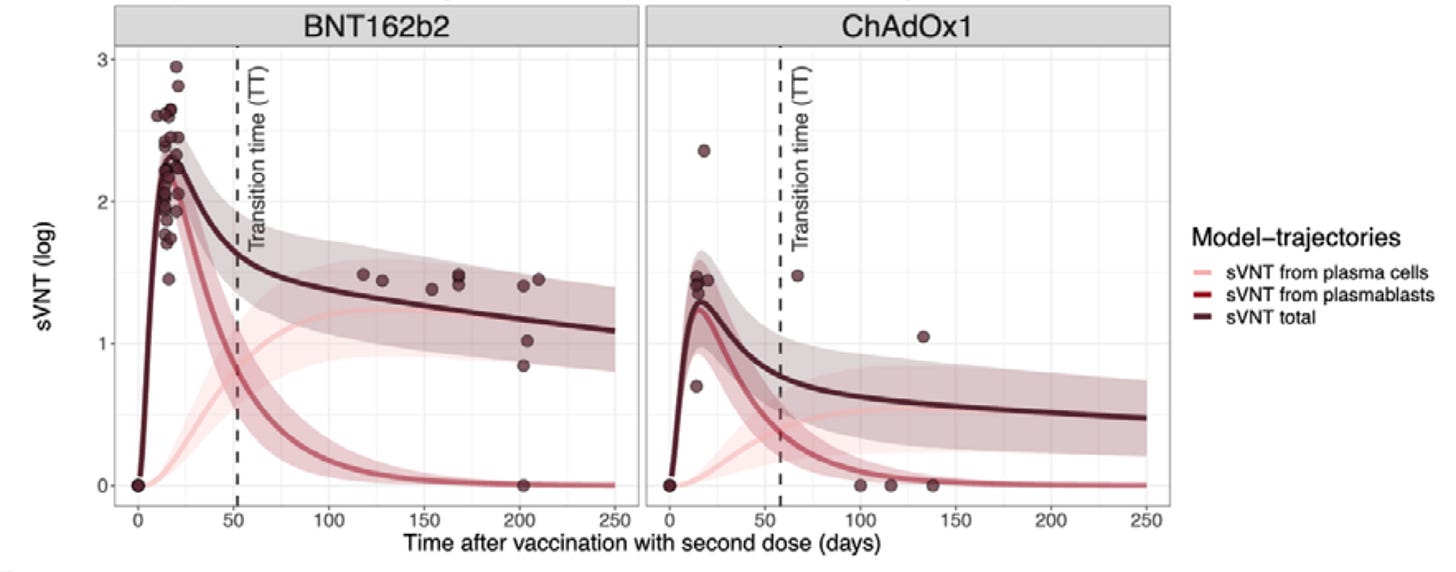

This pattern isn’t identical for all vaccines. By looking at the underlying components of the immune response, we’ve dug deeper into how and why different vaccines – like the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine, or Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 vaccine – may have generated different trajectories, but the overall ‘set point’ shape of the neutralising antibody trajectory after an initial post-boost decline is similar (dark line):

However, this decline to a set point antibody level after an initial boost doesn’t mean immunity wanes to negligible levels. When later cohort studies in 2020 and 2021 looked at the relationship between prior infection and subsequent re-infection risk with the same original variant or Alpha, they found that prior infection dramatically reduced the risk of another infection. This wouldn’t have been the case if overall immunity waned quickly for everyone.

2. The possibility of reinfection

Even by mid-2020, there was evidence that some people had caught COVID more than once. But as Marc Lipsitch and Bill Hanage put it in their useful piece early in the pandemic:

“Distinguish between whether something ever happens and whether it is happening at a frequency that matters.”

In 2020, the frequency of reinfections among those previously infected was very low compared to the frequency of infections among those yet to be infected, even after adjusting for the different group sizes. Reinfections with the same variant can happen, but they are relatively rare in terms of the overall number of infections.

A preprint by Ed Carr and colleagues found that there was a dichotomy in responses among those vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 – but not previously infected – in early 2021. As they put it:

“One group – broad responders – neutralize a range of SARS-CoV-2 variants, whereas the other – narrow responders – neutralize fewer, less divergent variants.”

In other words, reinfections can happen, and they seem to be more likely for a subset of individuals. But for many people, antibodies persist at high levels against past viruses, particularly after multiple exposures. For example, when we reconstructed titres after vaccination before the Delta wave hit, we found individuals with a prior infection had a larger and more persistent response against all variants:

3. Novel variants

What is a ‘reinfection’? The term has been the source of considerable ambiguity in media reports about COVID, especially after the emergence of novel variants.

Because variants like Delta and Omicron evolved in a way that evaded immunity built against earlier variants, it meant people could get infected with multiple COVID variants over time. It also meant that antibody responses after vaccination (which was designed for an earlier variant) might cross-react with other variants and be protective in the short term, but less helpful once these cross-protective responses had declined to a lower set point level.

This is one reason that vaccine effectiveness against variants like omicron appeared to decline so steeply over time. Another reason, though, is that vaccine effectiveness compared vaccinated with non-vaccinated individuals. And during omicron waves, many of the latter group were getting infected with a variant that was closer to the circulating one than the composition of the vaccine. In other words, it’s no longer a simple comparison of ‘potentially immune’ vs ‘non-immune’.

The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has led to many people having multiple infections. But it doesn’t mean that lots of people were getting multiple infections with the same variant. People are in general at much lower risk of reinfection if they are reexposed to the original SARS-CoV-2 variant. The new infections are therefore being driven mainly by the evolution of the virus, not the waning of variant-specific immunity.

The problem with a zombie statistic

The issue with these lingering misconceptions about waning immunity is they can feed into much larger flawed ideas. One persistent (but evidence-light) claim is that the first COVID wave in countries in the UK did not decline because of a dramatic reduction in social contacts, despite COVID being caused by an infection that spreads via social contacts. Instead, the claim is that COVID declined because a large proportion of the population had been infected and subsequently generated a strong immune response, albeit one that could not be detected even by the most sensitive antibody tests. Then, goes the logic, this invisible-but-strong immunity waned rapidly, allowing a second wave to take off.

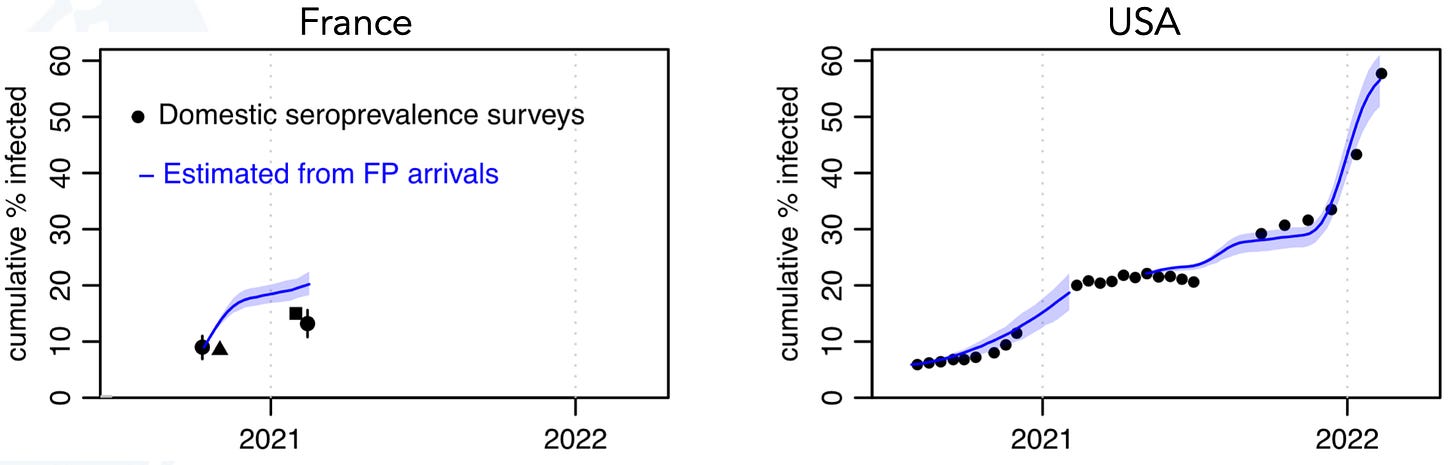

But, as we’ve seen above, immunity to the same variant didn’t wane rapidly. Nor is there evidence that later antibody studies are still missing lots of infections. For example, when we compared PCR testing among travellers from France and the US with those countries’ domestic antibody data, we found that the cumulative level of infection (blue lines) generally matched the trend we saw in the antibodies (black dots):

A useful analysis by Sam Abbott and Seb Funk found the same thing when they compared antibody levels over time with cumulative infections estimated from the ONS random PCR community testing study. In other words, there’s no evidence of a massive wave of infections that was missed in later antibody studies.

Another flawed claim relates to vaccines. The claim is that because people have persistent antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, there must be problem with the mRNA vaccines. If the zombie statistic about declining antibodies and immunity were true, and SARS-CoV-2 antibodies did usually wane rapidly to undetectable levels, then it would be unusual to detect them for months after a vaccine had been administered. But the above shows that antibodies persist in a ‘set point’ pattern following infection or vaccination for SARS-CoV-2, just like they do for other infections.

So for the sake of encouraging constructive discussions – and avoiding the inadvertent promotion of conspiracy theories – I think people need to stop suggesting otherwise.

My new book Proof: The Uncertain Science of Certainty is available to pre-order now.

Thanks Adam, probably also good to highlight that observations consistent with immune imprinting are likely due to selection bias :)

the misleading thing about this misleading thing is that "lingering immunity" is of no use whatsoever when the variant to which we have "lingering immunity" is extinct.

new variants replace those to which we had immunity REALLY FAST (see covariants.org for realtime illustrations). this is because we are breeding *so much* covid, and immune escape is a heavy evolutionary pressure on the virus. if it can't find hosts, it goes away. the immune-escaping ones are the ones in circulation; i.e. the ones that go right on infecting people.

so "lingering immunity" is kind of a lab curiosity? it's not stopping people getting sick. it is driving viral evolution more than stemming the pandemic. people are still getting sick, including with covid's particularly nasty and unpredictable long-term consequences, every day.

1 in 72 americans has covid RIGHT NOW: "lingering immunity" isn't doing much to help us.