Selective scepticism

From historial prayers to modern social media, the temptation is to cherry-pick evidence standards

In the 1870s, statistician Francis Galton became interested in whether prayer actually worked. As he saw it, the problem came down into ‘a simple statistical question – are prayers answered, or are they not?’

That meant finding some data to shed some light on the issue. In an 1872 paper, Galton settled on looking at the age of death; if people were being prayed for often, it should be possible to see a difference in survival. He noted that an obvious starting point would be royalty:

‘The public prayer for the sovereign of every state, Protestant and Catholic, is and has been in the spirit of our own, “Grant her in health long to live.” Now, as a simple matter of fact, has this prayer any efficacy?’

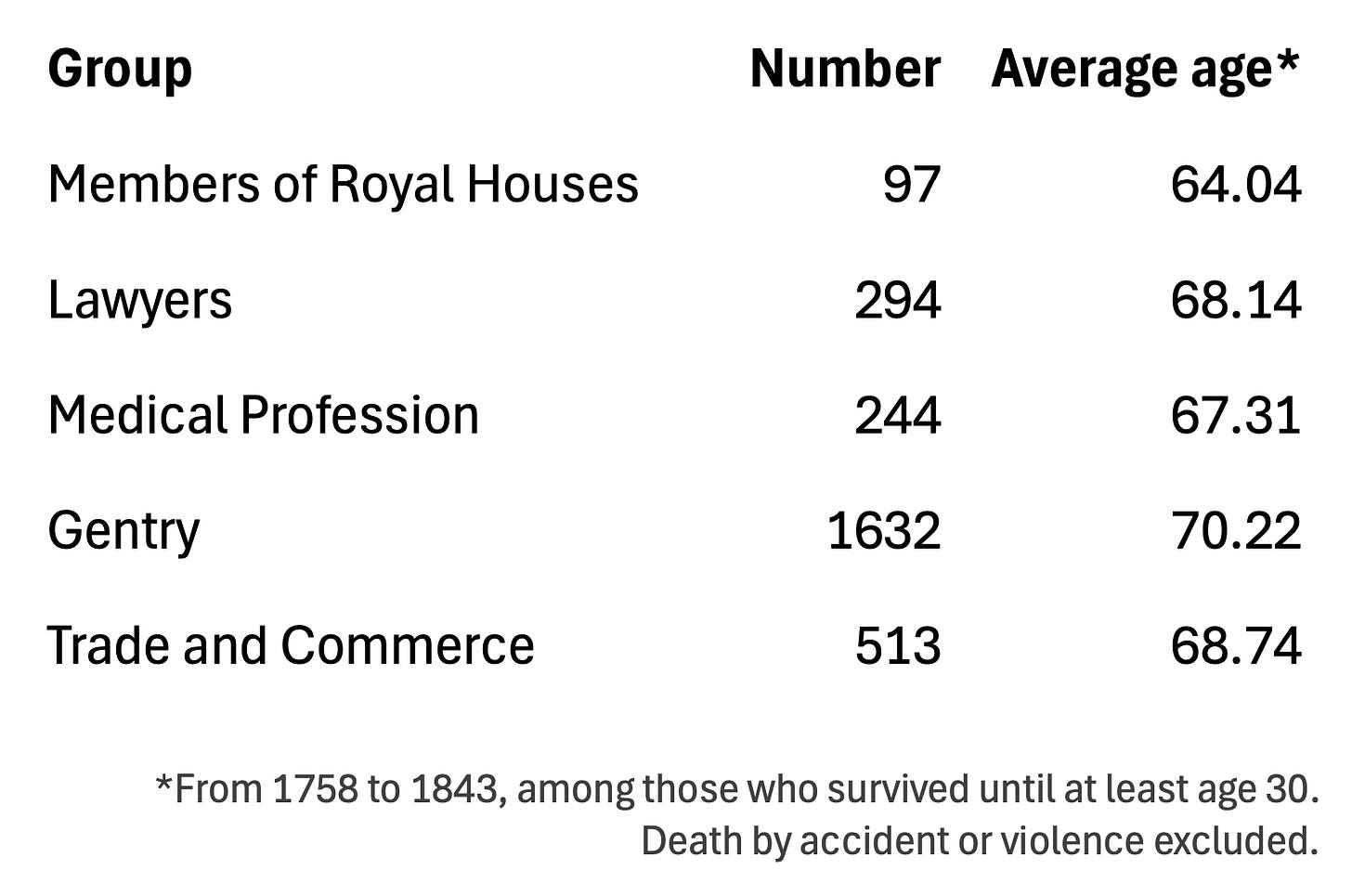

Drawing on data on mean age for different groups, Galton found that prayer didn’t seem to translate into longer life spans for royals:

To him, this was evidence against the theory that proclamations of ‘God Save the Queen/King’ were effective:

‘The sovereigns are literally the shortest lived of all who have the advantage of affluence. The prayer has therefore no efficacy, unless the very questionable hypothesis be raised, that the conditions of royal life may naturally be yet more fatal, and that their influence is partly, though incompletely, neutralized by the effects of public prayers.’

Galton didn’t stop with royalty. He also studied the lifespan of missionaries and the health of children in religious families, concluding that survival was ‘wholly unaffected by piety’. The analysis had a flippancy to it, and was far from rigorous, but it hit on an important statistical issue. Namely, how can we work out whether one thing is influencing another?

In his paper, Galton pointed out that people looking for an explanation in daily life would sometimes turn to science, while on other occasions they would rely on religion. He argued that the choice often depended on who was being asked and what they specialised in:

‘Most people have some general belief in the objective efficacy of prayer, but none seem willing to admit its action in those special cases of which they have scientific cognizance.’

In other words, a person’s belief – and scepticism – was selective, depending on the topic. This selectivity would also shape the views of Galton and his colleagues. Ever since Galton had read the work of his cousin, Charles Darwin, in the 1860s, he’d become fascinated by what influenced variation in human populations. He would eventually coin a new word – and scientific field – devoted to this subject. As he put it in 1883:

‘We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock… which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea.’

Galton’s protégé, Karl Pearson, would become the first holder of the Galton Chair in Eugenics at University College London. Pearson had made several crucial contributions to statistics – from correlation to p-values – and this apparent rigour was reflected in many of his statements. He once told his students about the value of Enlightenment philosophy:

‘Social facts are capable of measurement and thus of mathematical treatment, their empire must not be usurped by talk dominating reason, by passion displacing truth, by active ignorance crushing enlightenment’.

You might think that is an entirely sensible outlook to have. Yet Pearson’s focus on ‘social facts’ had led him to a view that successful nations came about by driving out what he called ‘inferior races’:

‘You will see that my view – and I think it may be called the scientific view of a nation – is that of an organized whole, kept up to a high pitch of internal efficiency by insuring that its numbers are substantially recruited from the better stocks’.

Pearson’s academic analysis of data, from roulette spins to coin flips, has mostly stood the test of time, unlike his outlook on how societies should function. Despite being famous for testing hypotheses, he did not challenge some of his own unsavoury beliefs.

Are you a selective sceptic?

The gap Galton described, between those beliefs we do and don’t challenge, still crops up today. Ever noticed how sceptical you feel when you read a news article about something you know well – spotting all the mistakes – but the moment you turn to a topic outside your expertise, you take it at face value? This paradox is called the Gell-Mann amnesia effect. Coined by author Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame), it reflects our tendency to forget the flaws we just spotted and trust the next piece of reporting as if the errors never happened.

Crichton named the paradox after Murray Gell-Mann, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist; the story goes that Gell-Mann himself had this habit1. When he read a newspaper article about physics, he’d often see that it was full of mistakes and simplifications. Then he’d flip the page to politics or another field, and switch his outlook, reading it as if this one must be accurate. ‘You turn the page, and forget what you know,’ as Crichton put it.

Selective scepticism can skew discussions of evidence, particularly on controversial topics. We see it when people insist that we should only accept ‘gold standard’ randomised controlled trials as evidence, but then quote ad-hoc anecdotes when their views about a claim are challenged. We also see it when people argue that clinical trials should focus on the overall effect of a treatment programme – including people who didn’t stick to it properly – but then claim that their preferred policy interventions are effective, it’s just the public don’t adhere to them. And we see it when people dismiss dozens of high quality studies, then believe someone’s false claims on a podcast because they’re a professor (albeit in a tangential subject).

I’ve previously written about why we’re bad at judging the strength of arguments we agree with:

Let’s say you have a strong belief about something. It could be enthusiasm for a particular film, or support for a political party. If you encounter evidence that aligns with your belief, you’ll walk away with a similar view, even if the evidence is weak. But what if someone makes an argument that challenges your belief? If it’s a weak argument, it won’t necessarily alter your opinion, but if it’s a watertight message delivered in a compelling way, it may well shift your attitude.

Selective scepticism can hinder our ability to process information effectively. But it can also be a useful way to spot flimsy claims. If a person’s standard for what counts as ‘good’ evidence varies inversely with how strongly they already believe something, then they may well be building arguments on a hope and a prayer.

Crichton also acknowledged that ‘by dropping a famous name I imply greater importance to myself, and to the effect, than it would otherwise have’.

When I'm fairly competent with a subject. i.e. I know how to check information presented. I tend to be more skeptical. When I don't know a subject, I tend to just absorb what is presented until I think I understand. then mull ideas over, checking the logic of the argument and testing with knowledgeable sources. In short, quick read, then musings.

I appreciate the topics that you discussed; to me it is relevant, interesting and challenging. This topic on selective skepticisms I think is very relevant these days.

Thank you Adam.