Wednesday morning is a weekly highlight for my toddler. He gets to wave at the recycling truck – and, to his delight, the men usually wave back. ‘TUCK! BYE BYE TUCK!’

The past couple of months have been an explosion of words. We’ve suddenly realised just how much he understands – and can now communicate. Which made me curious about how common such changes are, especially given how much experiences seem to vary from child-to-child.

I had a look at the Oxford CDI dataset from the late 90s and early 00s, which studied the number of common words spoken by children of different ages. One thing that immediately stood out was the amount of variation. Look at the words spoken by children aged around 18 months; it ranges from almost zero to over two hundred:

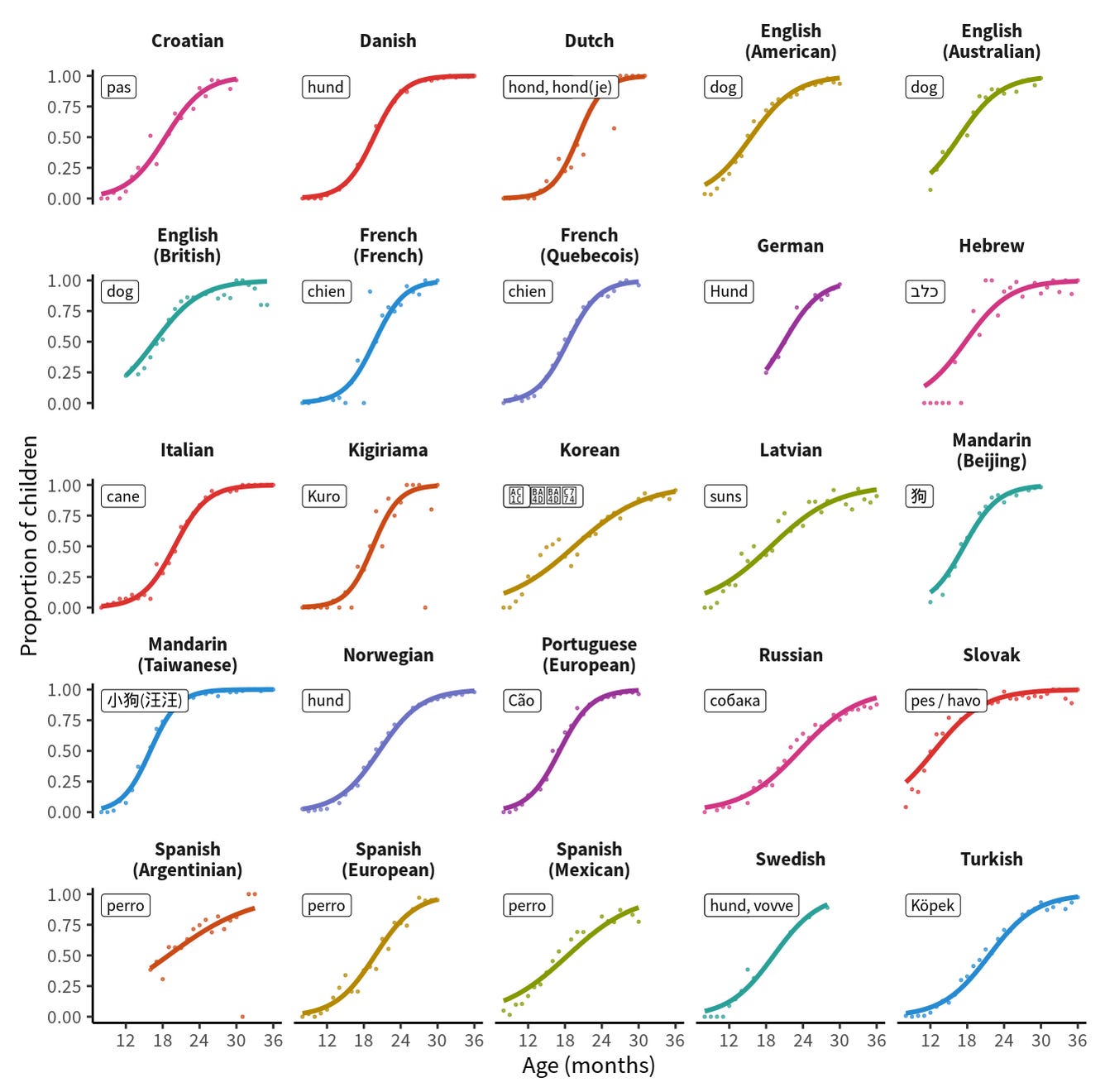

There’s lots more we can dig into when it comes to studies of words. Tom White has a nice visualisation of the order words are typically first spoken in a Norweigen dataset, starting with people (e.g. mummy, daddy) and routines (e.g. hi, bye) before moving onto nouns and verbs later on. Saloni Dattani has also highlighted the Wordbank resource, which has a range of interactive visualisations including comparisons across languages:

Doubling up

As well as single words, my son is also saying some words together. But often they come as a stock phrase – like ‘all gone’ – rather than being constructed of individual words. It turns out these so-called ‘frozen phrases’, where children say words together before using them individually, are common when children learn. One study estimated that around 20% of the first few dozen words are frozen phrases rather than single words.

Part of the reason seems to be efficiency in information storage. By ‘chunking’ words into phrases, children only need to remember the meaning of the phrase, rather than its underlying components. Chunking is also an important part of adult memory. A classic 1956 study by George Miller suggested that most young adults could learn and recite around seven numbers at a time (i.e. a phone number). Subsequent studies found that what Miller jokingly called the ‘magical number seven’ varies in reality, depending on the sort of information involved (e.g. single digits, larger numbers, or words). Chunking can therefore reduce the scale of information that must be memorised. Phone numbers often have digits grouped together to make them easier to remember, while students use mnemonics to recall key concepts.

But learning words isn’t just about the volume of information that can be stored. It’s also about what that information means.

Training sets

Pots, pans, dishes, ramekins. For a while my son called all of these ‘bowls’, which had two effects. First, it made me doubt my knowledge of what a bowl actually is. Does it depend on handles? Material? Size? Lid options?

Once my existential crockery crisis had subsided1, I got thinking about another aspect of learning. The rise of artificial large language models has been widely documented, with performance improving dramatically over the past year. Such models train on very large datasets until they are able to extract – and reproduce – meaning in everyday text. But how many words is a child trained on?

According to one study that recorded adult-child interactions, adults spoke around 12,000 words per day to young children on average (there aren’t unique words, of course; it’s been estimated the average American knows around 40,000 words, so they’d quickly run out). If this pattern holds, a typical child would have heard around 13 million words by the age of three. Which is quite a training set to go with their train set.

And a lot to ponder as we wait for this week’s recycling truck.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a bowl is ‘a round container that is open at the top and is deep enough to hold fruit, sugar, etc’. Which led me to the conclusion that nobody is totally sure what counts as a bowl, but we’ve all still learned to muddle along just fine.