What would you do to avoid norovirus?

And why doesn't the same caution apply to other seasonal infections?

“You know what, I really need to get a bout of norovirus this winter to top up my immunity.”

“Tell me about it, I didn’t get my annual hit of noro last year, and I’m worried my immune system is out of practice.”

“Yeah, it’s pointless trying to avoid it. Pass the potato salad, will you?”

This is not a conversation you’re ever likely to hear. And for good reason. Norovirus has some nasty symptoms, and as a result most people try to avoid it, even if it means cancelling gatherings or skipping events.

So why don’t people routinely have the same attitude to other seasonal viruses that spread from person-to-person? I often encounter claims that we need to get infections to ‘top up our immunity’, and it’s good for children to get exposed to bugs to ‘build up their immunity’.

The dynamics of immunity can be a counterintuitive and controversial topic. In the aftermath of COVID, there was a lot of debate – often at cross-purposes – about how a period of limited infections would affect subsequent epidemics. Last year, I wrote a piece explaining that if accumulated immunity and population turnover (i.e. new births) drive the epidemic patterns we see, then we’d expect COVID restrictions to temporarily disrupt the subsequent dynamics of other infections. But that doesn’t mean infections are a ‘good’ thing; it just means that this is the situation we’re currently in. And, perhaps, we could find our way to a different one in future.

Noro so different

Why are people so keen to avoid norovirus, rather than ‘top up’ their immunity to it? I suspect there are two main reasons:

Fast, distinct and unpleasant symptoms. Lots of seasonal infections cause symptoms that could be described as ‘a cold’ for many (as well as much more severe symptoms for a subset of people, of course). But norovirus’ distinctive symptom profile (it’s called ‘the winter vomiting bug’ for a reason), combined with short delay to onset of symptoms, make it clearer where – and who – someone got the virus from, and can drive a strong motivation to avoid getting it, and giving it to others, in future.

Cause-and-effect that can be disrupted. Norovirus is spread by close contact with someone who is infected, or via infected surfaces or food. Which gives people a sense of agency when it comes to avoiding it. If you’ve got a dinner planned and your friend has norovirus, you can either invite them round anyway and have a shit time (literally), or skip the meet up and dodge noro for a while. This perception of control over cause-and-effect seems to reduce the fatalistic attitude to other seasonal infections (“oh well, I’ll probably end up getting it anyway”).

There’s also a third reason to avoid norovirus, which is lesser known and hence probably less of a deciding factor than the above. Much like influenza and SARS-CoV-2, norovirus evolves over time, so immunity built up against earlier viruses becomes progressively less effective against new variants. As I’ve written about previously, this process of ‘antigenic drift’ leads to sequential replacement of the dominant variant over time, requiring influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to be updated. This will also be a key challenge for the new mRNA norovirus vaccine, which had a Phase 3 trial announced last month.

But reasons (1) and (2) might not be as strong as people think. Antibody studies suggest almost all adults have been exposed to norovirus, many without realising. This would suggest the symptom profile is much broader than many assume, and their ability to avoid it much smaller.

And yet, even after reading this evidence, I expect you’d probably still make the effort to try and avoid norovirus. We have enough grasp of the causes – and the effects – to intervene individually, even if our control of the risk is imperfect. Norovirus later is better than norovirus now. So, why not adopt this attitude for other infections too?

Soldiering on

During the acute phase of the COVID pandemic, I’d sometimes watch pre-COVID adverts for cold medicine to reflect on just how much attitudes had changed. Before COVID, marketing would focus on how you could suppress your symptoms and soldier on at your workplace, party or other social environment of choice. The below is just one of many examples you can find online:

As vaccines brought down the risk posed by COVID, we (rightly) saw some recalibration of how the infection was perceived. But many seem to be defaulting back to a pre-COVID outlook on seasonal infections, rather than thinking about how we could mitigate the damage of annual illness without the level of disruption seen during the worst months of COVID.

A recent IPPR report highlighted the UK productivity costs of presenteeism while sick, both in terms of direct effects (e.g. protracting recovery from illness) and indirect effects (i.e. spreading disease to others via ‘contagious presenteeism’). One 2019 study also modelled different sick leave strategies in Norway, and concluded that:

Prompt sick leave onset and a high proportion of sick leave among workers with influenza symptoms may be cost-effective, particularly during influenza epidemics and pandemics with low transmissibility or high morbidity

One of the likely reasons that Sweden was able to reduce COVID transmission with less stringent control measures than other European countries was its relatively generous sick leave package. Combined with a large proportion of single person households, this made it easier for people to isolate when ill, and not infect others while isolating.

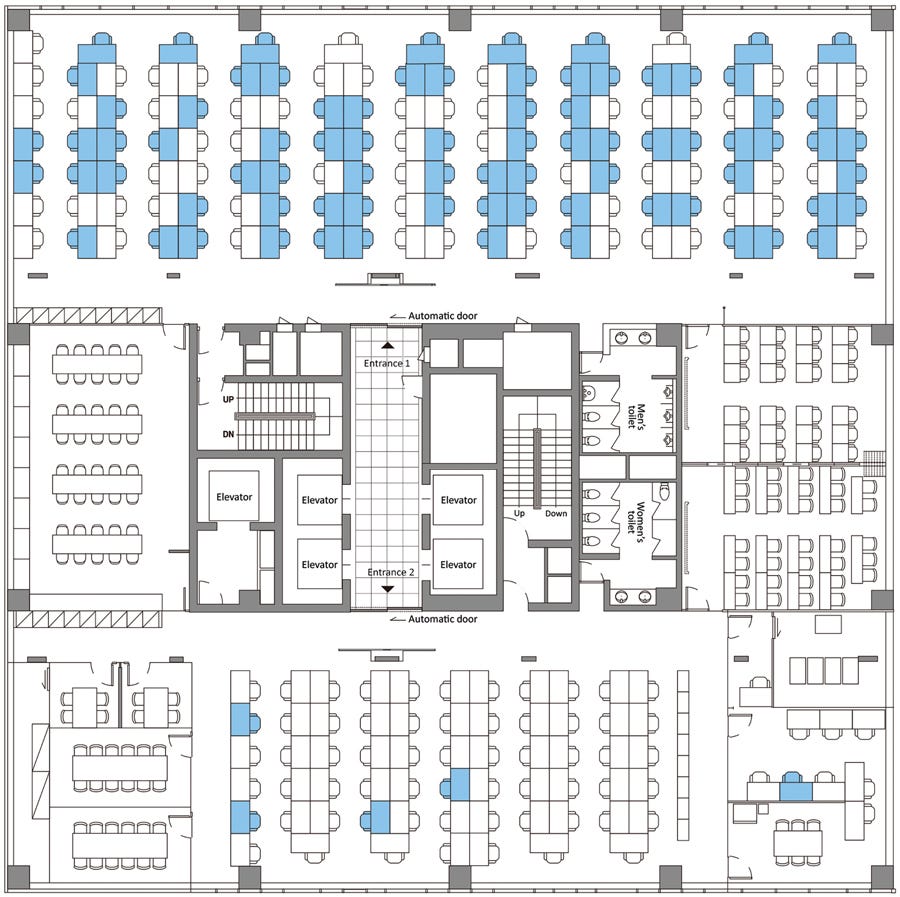

The below analysis of a March 2020 COVID outbreak in a South Korean call centre nicely illustrates how infection risk can cluster in workplaces (blue desks show those infected). Our ability to disrupt transmission in closed environments may therefore be much greater than many assume.

In recent weeks, there have been a few occasions where I’ve rescheduled meetings because the person I was meeting with had come down with flu or COVID. This seemed sensible: the cost of doing this was relatively low for us, and with a young baby at home, the cost of my picking up an infection was relatively high.

For other situations, the perceived cost of a change to routine still remains too high – whether missing an event, taking sick leave, or renovating our built environments – and the perceived benefits remain too low. But this shouldn’t be a reason to give up. Instead, we should find ways to reduce the disruptive effects of preventing infection, and build the evidence base required to show these changes are cost-effective, both at the individual and population level.

In other words, we need to make more seasonal infections like norovirus.

Cover image: CDC via Wikipedia

An Open Letter to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services

Your Top 8 Wildest Claims and Why Your Dangerous Pseudoscience Has No Place in Public Health

https://open.substack.com/pub/patricemersault/p/an-open-letter-to-robert-f-kennedy?r=4d7sow&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

> I often encounter claims that we need to get infections to ‘top up our immunity’, and it’s good for children to get exposed to bugs to ‘build up their immunity’.

Such claims are, I think, mostly wrong. But not always. I don't think people in the 19th century deliberately contracting cowpox were making a mistake. I also don't think (despite a tiny number of tragic deaths), that "chicken pox parties", pre-the-90s-vaccine, were actually a mistake. And getting live vaccines is, in essence, getting exposed to infections (albeit very mild ones) to build up an immunity.

I don't think people treat norovirus any differently to flu or covid. I certainly haven't seen any evidence of this. If anything, I worry less about catching noro than flu or covid, and would be less inclined to avoid meeting someone with it. I tend to experience mild symtpoms from stomach bugs, and if I do get anything, it's over in less than a day. Whereas covid can knock me out for at least a week.

Covid, in 2024, does not substantially change risk calculus on general infection avoidance from 2019. That doesn't mean 2019 behaviour was optimal, of course.